"WHEN THE BEATLES TOLD THE ROYALS TO RATTLE THEIR JEWELLERY" - THE MOMENT ROCK CONQUERED THE BRITISH ESTABLISHMENT

How Four Scruffy Liverpudlians Stormed the Gates of Privilege and Changed Pop Culture Forever

The Beatles' 1963 Royal Variety Performance represented the establishment's reluctant capitulation to youth culture

John Lennon's infamous "rattle your jewellery" quip became a subtle act of class rebellion that echoes through pop history

The unprecedented royal endorsement paved the way for decades of rock acts receiving establishment recognition

By Aidan Fraser-Jones March 25, 2025

The year is 1963. Britain is still clinging to post-war traditions. The Royal Variety Performance—that grand annual pageant of safe, sanitised entertainment for the monarchy—had never seen anything like The Beatles, and would never be the same again.

Looking back from our contemporary vantage point, it's difficult to comprehend just how seismic this cultural collision truly was. Before October 1963, when the announcement came that these scruffy Liverpudlians would perform for the Queen, the Royal Variety Performance had been the preserve of light entertainment stalwarts—genteel comedians, opera singers, and the occasional safely packaged pop crooner like Cliff Richard. Rock and roll acts were kept at arm's length from such prestigious establishments.

What strikes us most, sifting through the archives of that pivotal October BBC interview with Peter Woods, is the anarchic insouciance of these young men—barely into their twenties—as they contemplated performing for the monarch.

"Are you going to try and lose some of your Liverpool dialect for the Royal show?" the interviewer asks Paul McCartney, referencing Lord Privy Seal Edward Heath's sniffy complaint about their accents.

"No, are you kidding," McCartney fires back without hesitation. "We wouldn't bother doing that."

George Harrison, usually the quiet one, lands the killer blow: "We just won't vote for him."

This wasn't just cheek—it was a subtle declaration of class warfare. In Britain's rigidly stratified society, regional accents were markers of one's place in the social hierarchy. The Beatles refused to code-switch for the establishment, and in doing so, they dragged the monarchy into their world rather than conforming to royal expectations.

THE ROYAL OBSESSION: WHY IT MATTERED

The Royal Variety Performance, established in 1912, had always served as a kind of cultural gatekeeper, bestowing establishment approval on entertainers deemed acceptable for royal consumption. Previous rock-adjacent acts had been carefully vetted—Cliff Richard and The Shadows had appeared in 1960, but they were a sanitised, parent-friendly version of rock and roll, all smart suits and choreographed movements.

The Beatles represented something altogether different—authentic working-class culture with its own idioms, fashion, and attitude. They hadn't been processed through the usual channels of establishment approval.

What's remarkable in retrospect is how conscious The Beatles themselves were of this cultural tension. When Woods asks how long they expect their success to last, George Harrison offers a telling comparison: "If we do as well as Cliff and The Shadows have done up to now, well I mean, we won't be moaning."

The comparison is pointed—Cliff Richard had managed to maintain longevity by working within the system. The Beatles, though they didn't yet know it, would transform that system entirely.

"I mean, naturally, it can't go on as it has been going the last few months. It'd just be ridiculous," Harrison continues, in a moment of delicious historical irony. Their trajectory would not only continue but accelerate beyond anything British pop culture had previously experienced.

THE PERFORMANCE THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

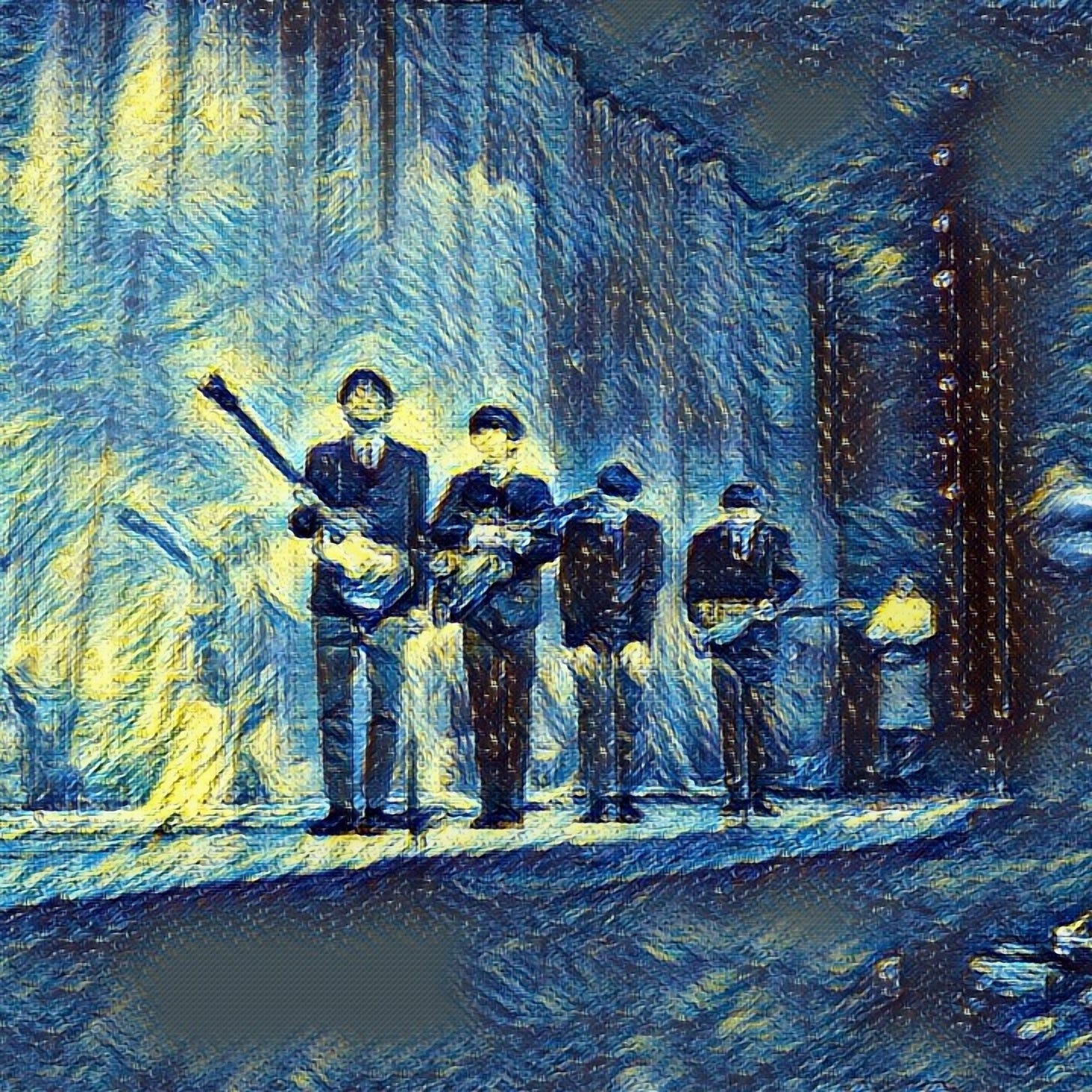

When The Beatles finally took the stage at the Prince of Wales Theatre on November 4, 1963, they delivered a performance that would become legendary not just for the music but for John Lennon's subversive introduction to "Twist and Shout": "For our last number, I'd like to ask your help. The people in the cheaper seats, clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you'd just rattle your jewellery."

This line—not captured in the BBC radio interview but now seared into cultural memory—perfectly encapsulated The Beatles' approach to the establishment. Respectful on the surface, revolutionary underneath.

Brian Epstein, their manager, had reportedly been terrified about what Lennon might say. The original version of the quip, according to Paul McCartney years later, was far more provocative: "Rattle your fucking jewellery." Lennon toned it down, but the message remained clear: class consciousness delivered with a smile.

THE RIPPLE EFFECT

The Beatles' Royal Variety appearance created a template for rock acts navigating the establishment. In the years that followed, the Royal Variety Performance would host increasingly adventurous acts: The Rolling Stones (1966), The Who (1970), and eventually, even punk-influenced performers.

By 1977, the Sex Pistols would take the Beatles' subtle subversion to its logical extreme, releasing "God Save the Queen" during the Silver Jubilee. Without The Beatles' initial breach of the palace walls, such a direct assault might never have been conceivable.

What's striking about The Beatles' approach in that October interview is their refusal to be overawed. When asked how much of their success is due to musical talent, McCartney responds with disarming honesty: "Uhh, dunno. No idea. You just can't tell, you know. Maybe a lot of it, maybe none of it."

There's something quintessentially Liverpudlian about this resistance to self-aggrandisement. Unlike American rock stars with their swagger and boasting, The Beatles maintain a wry detachment from their own fame—a quality that paradoxically made them even more appealing.

THE HAIRCUTS HEARD 'ROUND THE WORLD

"But your funny haircuts aren't natural?" Woods asks in the interview.

"Well, we don't think they're funny, ya see... cobber?" John Lennon responds in a comical voice.

That simple exchange exemplifies the culture clash at work. To the establishment, The Beatles' moptops were an aberration, a deviation from proper grooming standards. To the band and their fans, these haircuts were a badge of identity—a visual representation of their refusal to conform.

By the time they appeared on the Royal Variety Performance, those haircuts had become a cultural signifier potent enough to cause moral panic among the older generation. Schools banned the style, parents threatened to disown sons who adopted it, and newspapers ran alarming stories about the corrupting influence of "Beatlemania."

Looking back from 2025, when pop stars regularly sport far more outlandish styles without comment, the controversy seems quaint. But those four fringes represented a genuine challenge to post-war Britain's rigid conformity.

THE SCREAM HEARD 'ROUND THE WORLD

"How do you find all this business of having screaming girls following you all over the place?" Woods asks in the interview.

"Well, we feel flattered," George responds.

"...and flattened," John adds, prompting laughter.

The Beatles' female fans were another source of establishment anxiety. Young women's public displays of desire and abandon threatened the carefully maintained facade of proper British restraint. When The Beatles performed at the Royal Variety Performance, they brought this unbridled feminine energy into the royal orbit.

The screaming wasn't just about music—it was a collective expression of female liberation. In stuffy 1963 Britain, these young women were claiming public space for their desires in unprecedented ways. By acknowledging and even celebrating this phenomenon, The Beatles aligned themselves with feminine power at a time when that was still culturally radical.

THE LEGACY OF LIVERPUDLIAN DEFIANCE

Perhaps the most significant aspect of The Beatles' Royal Variety breakthrough was how it validated regional identity in British culture. Liverpool—a working-class port city often derided by the London-centric media—suddenly became the epicentre of British cool.

When Paul McCartney mockingly adopts an upper-class accent in the interview, saying, "We don't all speak like them BBC posh fellas, you know?" he's doing more than making his bandmates laugh. He's pointing out the class coding embedded in British broadcasting and, by extension, in British society itself.

Post-Beatles, regional accents would increasingly appear in mainstream British media. The cultural dominance of Received Pronunciation (the "Queen's English" that so troubled Edward Heath) began its slow decline. By the 1990s, Britpop bands like Oasis would take The Beatles' regional pride to new extremes, deliberately emphasising their Mancunian accents rather than trying to neutralise them.

THE ROYAL VARIETY PERFORMANCE TODAY

Today, in 2025, the Royal Variety Performance continues, though it exists in a cultural landscape unrecognisable from 1963. Recent performers have included grime artists, K-pop groups, and LGBT+ performers—a diversity that would have been unimaginable when The Beatles took that stage.

What remains consistent is the tension between establishment decorum and pop cultural vitality. Every performer who takes that stage must navigate the same territory The Beatles did—how to maintain authenticity while performing in an inherently establishment context.

Few have done it with the charm, wit, and subtle subversion that those four Liverpudlians brought to the task.

THE INTERVIEW THAT FORESHADOWED A REVOLUTION

Reading the transcript of that October 1963 BBC interview today, what's most striking is how much The Beatles' responses foreshadow the cultural revolution they would help catalyse. Their refusal to take themselves too seriously, their class consciousness, their rejection of establishment norms—all these elements would become central to their evolving identity as artists.

When they sang "She Loves You" before the Queen a month later, they weren't just performing a pop song—they were announcing a new cultural order, one where young working-class voices couldn't be ignored or marginalised.

From our vantage point in 2025, as we look back at the six decades of British popular music that followed, we can clearly see the fault line that The Beatles created. Before them, pop culture and establishment culture existed in separate worlds. After them, the two would remain in constant, productive tension—sometimes collaborating, sometimes conflicting, but never again ignoring each other.

That's the true legacy of those four lads from Liverpool who refused to change their accents for the Queen.