The Chelsea Flower Show Chronicles: When Two Beatles Bloomed Amongst the Roses

The world spins through millennial madness, Little Richard spills unflattering secrets, and the great 'Hey Bulldog' controversy reaches its predictable conclusion

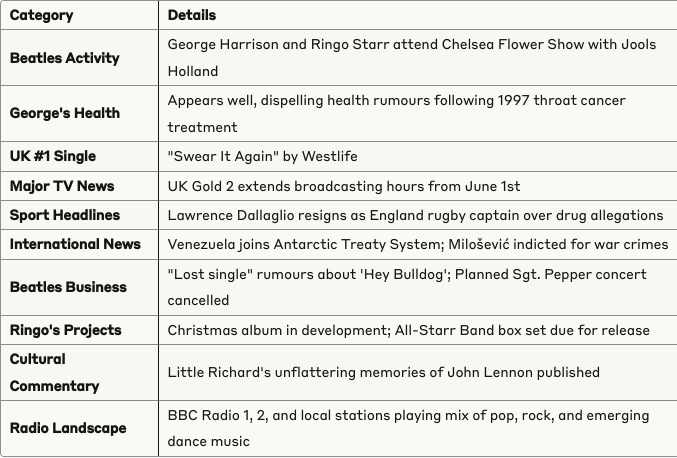

There's something quintessentially mad about finding two former Beatles wandering through the Chelsea Flower Show on a Monday morning in May, like characters who've wandered out of a particularly English fever dream. George and Ringo, accompanied by their friend Jools Holland, attend the opening of the annual Chelsea Flower Show in London. George, wearing a short haircut, looks extremely well, dispelling rumours of his poor health. But there they were on May 24th, 1999, three unlikely gardening enthusiasts sniffing around prize-winning delphiniums whilst the rest of the world spun through its peculiar millennial anxieties.

George Harrison looked particularly well that morning, which was rather the point, wasn't it? The man had been through the medical wringer over the previous eighteen months, enduring that special kind of hell reserved for former rock stars who'd spent decades smoking their way through the consciousness-expanding sixties only to discover that enlightenment comes with rather more mundane consequences than anyone had bargained for.

The Weight of Waiting Rooms

The fears about George's health weren't exactly media fabrications. Harrison was diagnosed with throat cancer; he was treated with radiotherapy, which was thought at the time to be successful. He publicly blamed years of smoking for the illness. The quiet Beatle had discovered a malignant nodule on his throat in 1997, leading to that grim choreography of hospital visits, radiation treatments, and the peculiar optimism that accompanies successful cancer treatment. By January 1998, after follow-up tests at the Mayo Clinic confirmed that the cancer had not returned, Harrison expressed relief and gratitude for receiving a clean bill of health.

But cancer, like fame, has its own timetable, and the public appetite for Beatles mortality updates had reached fever pitch by spring 1999. Every public appearance was scrutinised for signs of decline, every photograph examined for evidence of the inevitable. So there was George at Chelsea, looking robust and almost aggressively healthy, his newly shorn hair catching the morning light as he navigated between prize-winning roses and the curious stares of fellow flower enthusiasts.

Ringo, meanwhile, was in that curious post-Beatles limbo that had become his permanent address – still drumming, still touring with his All-Starr Band, still wearing those tinted glasses that had become as much a part of his identity as his distinctive snare sound. Planned for release this month by the Eagle Rock label in America is a 3 CD box set featuring a compilation of live All-Starr Band recordings taken from the last ten years. The man was nothing if not prolific, even if his audience had shrunk to the sort of people who attended charity golf tournaments and corporate events in Atlantic City.

The Botanical Brotherhood

The choice of the Chelsea Flower Show as a venue for this impromptu Beatles reunion was perfectly absurd in its Englishness. Here was the annual celebration of horticultural excellence, where retired colonels argued about prize-winning begonias and middle-class housewives plotted elaborate water features for their suburban gardens. And wandering through it all, two-quarters of the most famous band in history, accompanied by Jools Holland – that piano-playing magpie who'd somehow transformed himself from Squeeze member to national treasure through sheer force of enthusiasm.

The timing was curious too. May 1999 found Britain in a strange transitional state, caught between the optimism of New Labour's early years and the approaching uncertainty of the new millennium. The number 1 song in the UK on May 24, 1999 was Swear It Again by Westlife, which tells you everything you need to know about the state of popular music at the time. Boy bands had conquered the charts with the sort of manufactured sincerity that would have made the Beatles simultaneously laugh and weep.

The Lost Single Circus

Meanwhile, the Beatles industry continued its relentless march, grinding out repackaged nostalgia and manufactured controversy with the efficiency of a Victorian textile mill. The American Ice magazine hints that the supposedly "lost Beatles single" will actually be a new version of the 1968 track 'Hey Bulldog'. The great lost single saga had been rumbling on for months now, generating the sort of breathless speculation usually reserved for royal pregnancies or football transfers.

The whole affair had the distinct whiff of corporate desperation about it. Here were the surviving Beatles, or their representatives, attempting to wring fresh magic from forty-year-old sessions, like archaeologists trying to reconstruct dinosaurs from a single vertebra. A spokesman for The Beatles admits defeat, announcing: "It's not undiscovered, like 'Free As A Bird' or 'Real Love'. But it is lost in that it's probably the most overlooked song in the entire Beatles catalogue".

The meta-commentary was almost more interesting than the music itself. The spokesman's admission of defeat contained within it the entire post-Beatles predicament – how do you follow perfection? How do you satisfy an audience whose expectations have been shaped by the impossible standard of your own past work?

Television's Peculiar Monday

May 24, 1999 was a Monday, which meant that British television was serving up its usual mixture of children's programmes, daytime chat shows, and the sort of gentle documentary programming that filled the spaces between more serious endeavours. The Digital Spy website reports that UK Gold 2 is to have its broadcasting hours extended from 1 June. The channel has operated on a limited basis, airing on Fridays to Sundays from 6pm to 2am, but will become a daily service.

The expansion of UK Gold 2 was symptomatic of television's growing obsession with its own past. Here was a channel dedicated entirely to reruns, extending its hours to feed an apparently insatiable appetite for yesterday's programmes. It was the televisual equivalent of the Beatles reissue industry – an endless recycling of past glories for an audience increasingly suspicious of anything new.

The morning would have been filled with the usual suspects: breakfast television presenters maintaining their relentless cheerfulness in the face of another Monday, children's programmes featuring characters whose names would be forgotten within a decade, and the gentle hum of daytime programming designed to offend nobody and engage even fewer.

Cultural Crosscurrents

The pop culture landscape of May 1999 was a strange beast indeed. Lawrence Dallaglio resigns after a tabloid newspaper accused him of having taken drugs, which was the sort of manufactured scandal that had become the media's bread and butter. Meanwhile, Manchester United complete a unique treble of major trophies when they defeat Bayern Munich of Germany 2–1 in the European Cup final two days later, providing the sort of genuine drama that made the tabloid fabrications seem even more pathetic by comparison.

The radio waves would have been filled with Westlife's saccharine harmonies, competing with the last gasps of Britpop and the emerging dominance of manufactured pop. This was the era when record companies had perfected the art of creating stars from focus groups and market research, producing music with all the authenticity of a political campaign promise.

In an interview for BBC radio, Tom Petty announces that he intends to revive The Traveling Wilburys, the group that once featured himself alongside George, Bob Dylan, Jeff Lynne and the late Roy Orbison. The irony was delicious – here was Tom Petty planning to resurrect a supergroup that had existed largely for the joy of collaboration, whilst the original Beatles couldn't manage to occupy the same flower show without generating newspaper columns about George's health.

The Ghosts of Rock and Roll Past

The most unsettling element of the day's Beatles-related news came from an unexpected source. In an edition of the magazine The Week, Little Richard speaks about John Lennon, remembering him as "pure misery!" He also goes on to say about the former Beatle: "If I had a stick I think I might have beat him with it. He would do horrible things, like get you in a little room, pass gas, and run out and lock you in".

Little Richard's reminiscence provided an oddly humanising counterpoint to the endless Beatles hagiography. Here was one of rock and roll's founding fathers describing John Lennon not as a peace-loving icon but as a juvenile prankster with a disturbing fondness for flatulence-based humour. It was the sort of detail that punctured the mythology surrounding the band, revealing them as the collection of overgrown adolescents they'd always been.

The timing of these revelations was particularly pointed, coming as they did on the same day that George was making his carefully choreographed public appearance at Chelsea. The contrast between Little Richard's scatological memories and the genteel world of prize-winning roses couldn't have been more pronounced.

The Millennium's Approaching Shadow

May 1999 carried with it the weight of approaching change. The millennium celebrations were still months away, but already there was a sense of ending, of chapters closing and new ones preparing to open. Venezuela joins the Antarctic Treaty System and Slobodan Milošević and four others are indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Kosovo – the world was reshaping itself whilst two former Beatles wandered through a flower show, temporarily immune to the larger currents of history.

The news headlines spoke of endings and beginnings. The Kosovo conflict was grinding towards its conclusion, with NATO's bombing campaign finally forcing Serbian forces to withdraw. The indictment of Milošević represented something new in international justice – the idea that political leaders could be held accountable for their actions, regardless of their power or position.

The Quiet Revolution of Ordinary Days

There's something to be said for the way extraordinary people navigate ordinary days. Here were George and Ringo, two men who'd helped reshape popular culture, spending a Monday morning looking at flowers. The very mundaneness of it was revolutionary in its own way – a quiet rejection of the idea that fame requires constant performance.

The Chelsea Flower Show represented a peculiarly English form of escapism. Whilst the world grappled with war crimes and cultural upheaval, here was a space dedicated entirely to the cultivation of beauty for its own sake. The prizes were awarded not for commercial success or critical acclaim, but for the simple achievement of making something grow better than anyone else had managed.

George's presence there, looking healthy and unremarkable, was perhaps the most radical statement he could have made. After years of being scrutinised for signs of decline, here he was, participating in the most ordinary of English rituals – the appreciation of well-tended gardens and the gentle competition of horticultural excellence.

The Persistent Echo of Yesterday

The Beatles phenomenon had always been about more than music. It was about the promise that four ordinary young men could transform themselves into something extraordinary, that talent and timing could overcome any obstacle. By 1999, that promise had curdled somewhat, transformed into an industry dedicated to packaging and repackaging past glories for successive generations of consumers.

The planned Sgt. Pepper's concert in London (revealed on November 17 last year) fails to materialise, which was probably for the best. The idea of recreating one of rock's greatest achievements for a nostalgic audience represented everything that was wrong with the way the Beatles legacy had been managed – the endless attempt to recapture magic that had been spontaneous the first time around.

Ringo's Christmas album plans were more honest in their modesty. When asked about this, Ringo replies: "It'll be very Christmassy and lots of bells, ding, ding, ding". There was something refreshing about the straightforward acknowledgment of what the project would be – seasonal music for people who wanted to hear Ringo Starr sing Christmas songs. No pretense of artistic breakthrough, no claims of lost masterpieces. Just bells, ding, ding, ding.

The Endless Appetite for More

The most striking aspect of the Beatles story in May 1999 was the relentless hunger for new material from a band that had officially ceased to exist nearly thirty years earlier. The 'Hey Bulldog' controversy represented the increasingly desperate measures being taken to satisfy this appetite, scraping the barrel of unreleased material for anything that might constitute a 'new' Beatles recording.

The fact that the missing verse cut from the original recording, but actually recorded and released in 1971 by the all-female rock group Fanny suggests the lengths to which Beatles archaeologists were prepared to go. Here was a verse that had been deemed unworthy of inclusion on the original recording, rescued from obscurity and presented as a lost treasure simply because it bore some tangential relationship to the Beatles canon.

The industrial nature of Beatles nostalgia had reached the point where even the band's cast-offs were being recycled as premium content. It was cultural capitalism at its most efficient – nothing could be allowed to go to waste if there was even the slightest possibility of extracting commercial value from it.

The day would end as it began, with two former Beatles returning to their respective lives, having spent a few hours in the company of flowers and the sort of people who found deep meaning in the proper cultivation of prize-winning begonias. In a world increasingly dominated by manufactured controversy and recycled culture, it was perhaps the most subversive thing they could have done – simply showing up, looking well, and participating in something that had nothing whatsoever to do with being Beatles.