The Beatles Return to Charts as Forgotten Critics Are Fondly Remembered

Physical singles make comeback whilst forgotten critics emerge from shadows

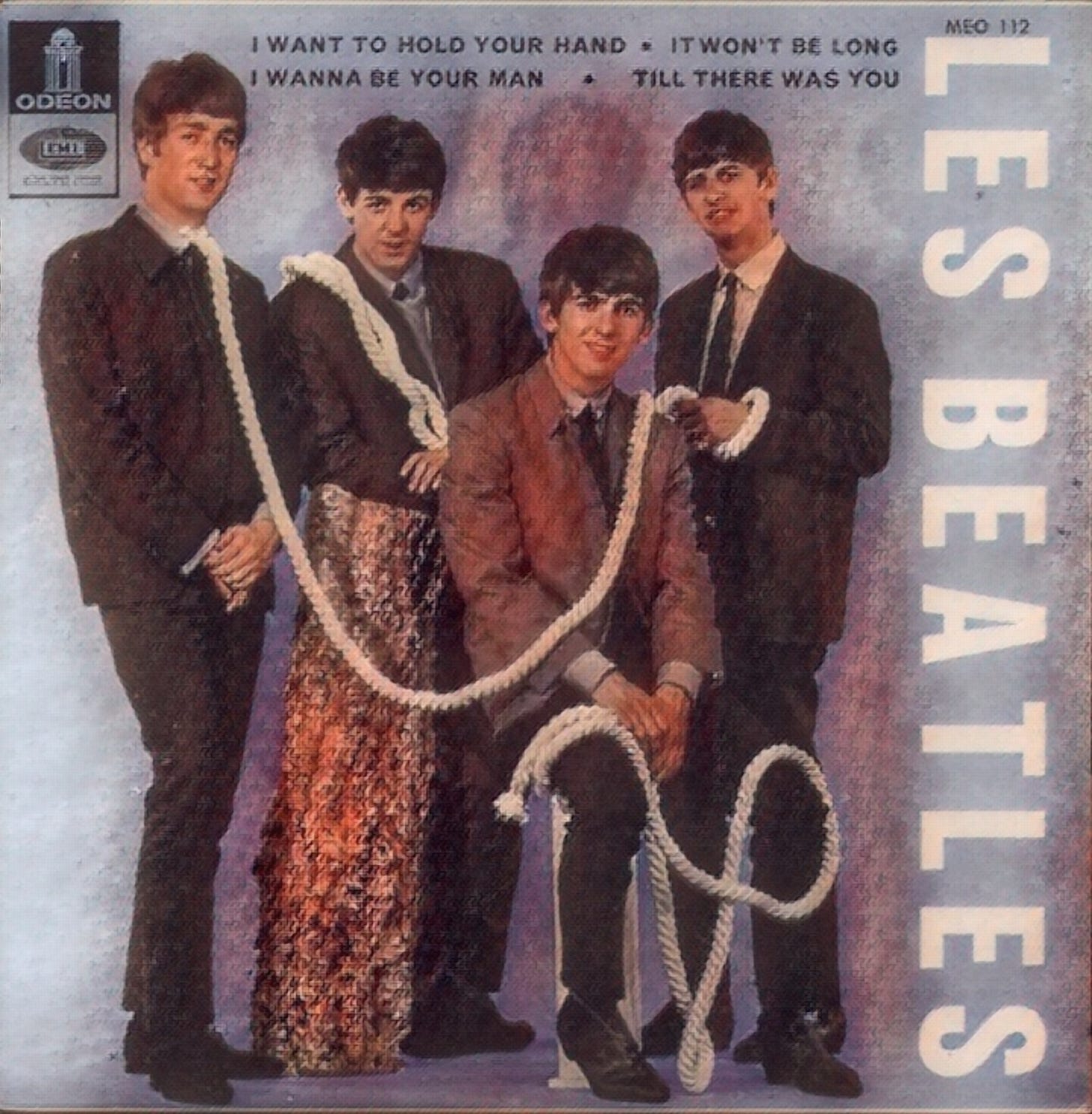

Two Beatles tracks re-enter UK Physical Singles chart with "From Us to You" climbing higher than "I Want to Hold Your Hand"

New book explores Lennon-McCartney relationship through their songs, revealing deeper emotional connections

Tributes pour in for journalist who famously panned early Beatles gig, calling them unexciting in scathing 1962 review

Well, well, well. Here we are again, watching the Fab Four climb back up the charts like some sort of musical Lazarus, refusing to stay buried beneath the avalanche of contemporary pop pap that passes for music these days. This week sees two Beatles singles crawling back onto the Official Physical Singles chart, proving that in an era of streaming supremacy, there are still enough people with functioning taste buds willing to part with actual money for actual records.

"From Us to You" has sauntered back in at number 53, whilst "I Want to Hold Your Hand" trails behind at a rather pedestrian 74. One might wonder what's prompted this sudden rush to the record shops - perhaps it's the same inexplicable urge that makes people queue for hours to buy overpriced coffee, or maybe it's simply that quality will out, as it always does.

The irony isn't lost that "From Us to You" - not to be confused with its more famous sibling "From Me to You" - has outperformed the track that once sat pretty at number two. It's rather like watching the understudy steal the show from the leading man, though in this case both performers happen to be dead and their understudies are vinyl pressings.

Meanwhile, their compilation albums continue to lumber about the charts like well-fed elephants at a tea party. The "1962-1966" collection has parked itself at number 97 on the Official Albums chart, whilst also claiming the 92nd spot on the streaming list. Its partner in crime, "1967-1970", has managed a slightly more respectable showing at 64 and 56 respectively. One can only assume that somewhere in Britain, there are people discovering that the Beatles made music after "Love Me Do" and before "Let It Be" - a revelation that would doubtless have amused the lads themselves.

But perhaps the most intriguing footnote in this week's Beatles buffet comes courtesy of the recently departed Lyndon Whittaker, a respected Peterborough journalist whose 1962 review of an early Beatles gig has achieved a certain immortality. Back when the lads were still relatively unknown quantities supporting Frank Ifield at the Embassy Theatre, Whittaker offered what history would judge as a rather premature assessment.

The Beatles, he declared with the measured tone of a professional critic, "quite frankly failed to excite me." He noted they "sounded as though everyone was trying to make more noise than the others" and observed of Ringo that "the drummer apparently thought his job was to lead, not provide the rhythm. He made far too much noise."

Now, it's worth remembering that in 1962, precious few people could have predicted that four lads from Liverpool would still be shifting units six decades later. Whittaker was simply doing his job as a local critic, reviewing what he heard on the night - and by all accounts, early Beatles gigs could be rather chaotic affairs before they found their stride.

The charming irony is that Whittaker himself was apparently more embarrassed about his praise for Frank Ifield than his dismissal of the future Fab Four. When he later interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono during their Amsterdam bed-in in 1969, he diplomatically chose not to mention his earlier review - probably a wise editorial decision given John's capacity for memorable putdowns.

What's rather touching about the whole affair is that Whittaker, who went on to become a beloved mentor to countless young journalists throughout his career, never lived down this moment of spectacularly unfortunate timing. It's become part of Beatles lore - and really, there are worse ways to achieve a sort of immortality than being wrong about the most successful band in history. At least he was there, pen in hand, doing the honest work of journalism when history was being made.

Speaking of people who understood the Beatles rather better than poor Lyndon, we have Ian Leslie's new tome "John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs," which promises to examine the Lennon-McCartney partnership through the lens of their musical output. Leslie argues that previous Beatles biographies have either recounted facts without doing justice to the music, or failed to explore the pair's relationship with sufficient "emotional intelligence" - a phrase that would have made John curl his lip in disdain.

The book apparently suggests that songs like "Jealous Guy" weren't necessarily about romantic relationships but rather about John's complex feelings towards Paul - which, if true, adds several layers of psychological complexity to tracks we thought we knew inside out. Leslie even claims that Paul's "Coming Up" was essentially a musical olive branch extended to his former partner, whilst "Starting Over" represented John's own tentative steps towards reconciliation.

Whether one buys into this rather intense psychological analysis or dismisses it as over-interpretation depends largely on one's tolerance for finding deeper meaning in pop songs. John himself was always rather sceptical about people reading too much into his lyrics, though he was equally capable of loading them with multiple meanings when it suited him.

The influence of the Beatles continues to ripple outward like stones thrown into a pond, with everyone from Frank Ocean to Taylor Swift claiming the Fab Four as inspiration. Gene Simmons of Kiss has declared them superior to anything produced in the last 200 years, which coming from a man who breathes fire and wears platform boots the size of small cars, carries a certain weight.

Even America's Got Talent has got in on the act, with contestant Charity Lockhart earning a golden buzzer for her rendition of "Golden Slumbers." The fact that a Beatles song can still stop a talent show in its tracks in 2025 suggests that reports of their cultural death have been greatly exaggerated.

Perhaps most intriguingly, we learn about Vee-Jay Records, the Chicago-based, Black-owned label that first brought the Beatles to America with "Introducing the Beatles" - a full ten days before Capitol's "Meet the Beatles" hit the shelves. The subsequent legal battle between the two labels reads like a David and Goliath story, except in this version David gets crushed by the giant's superior resources despite being technically in the right.

Calvin Carter's recollection of going from 15 employees to 200 overnight, selling 2.6 million Beatles singles in a month, only to watch the company collapse under the weight of its own success, feels like a particularly American tragedy. Vee-Jay's story deserves better than the footnote status it's been relegated to, much like poor Lyndon Whittaker deserved better than to be remembered primarily for his critical blind spot.

As for Wings getting their due recognition, well, that's a battle that's been raging for decades. "Band on the Run," "Let Me Roll It," and "Arrow Through Me" are indeed fine songs that suffer mainly from not being Beatles tracks. It's the eternal curse of being Paul McCartney - everything you do after the Beatles will inevitably be measured against "Yesterday" and "Hey Jude," which is rather like judging a perfectly good roast dinner against the memory of the best meal you've ever eaten.

The White Album continues to fascinate, with its hidden tracks, real-life inspirations, and the delicious gossip about Yoko's presence in the studio causing ructions amongst the other three. The fact that Paul played drums on "Back in the USSR" and "Dear Prudence" whilst Ringo was off having a sulk on a boat adds another layer to the album's fractured creation story.

John Lennon's own views on talent and genius, as captured in Hunter Davies's authorised biography, provide a fascinating counterpoint to all this reverence. "We're not better than anybody else," Lennon insisted back in 1968. "We're all the same. We're as good as Beethoven. Everyone's the same inside." It was typical John - equal parts profound and provocative, designed to puncture the growing mythology around the band whilst they were still very much alive to witness it.

His assertion that "what's talent? I don't know" and that "the basic talent is believing you can do something" feels particularly relevant when considering the current crop of Beatles-influenced artists. Whether it's Billie Eilish learning songcraft from "I Want to Hold Your Hand" as a child, or Frank Ocean sampling "Here, There and Everywhere" for his own creative purposes, the thread connecting these artists isn't some mystical transmission of genius - it's simply the belief that they too can create something worthwhile.

Lennon's later clarification in a 1968 university interview adds nuance to his earlier dismissal of talent: "I made it because I'm me and I have that thing that makes music and makes those songs up. I believe everybody has got something. They've just got to bring it out." It's a more generous view than his initial "we're all cons" position, though he maintained that anyone claiming to understand the deeper meaning of Beatles songs was talking "drivel."

This tension between meaning and meaninglessness runs through much of the current Beatles discourse. Leslie's book suggests that "Jealous Guy" might be about Paul rather than a romantic partner, whilst Paul's own "Coming Up" could be read as a plea for reconciliation. But as Lennon himself noted, these interpretations often say more about the interpreter than the songs themselves. "Dylan knows where it's at in regard to our songs and what people liked about them," he observed, "and that is the 'con' job."

The persistence of Beatles samples in modern music - from Wu-Tang Clan to Mac Miller to Drake - suggests that the "con" is working as well as ever. When Frank Ocean credits the Beatles with helping him overcome writer's block, or when Dave Grohl insists he "would not be a musician" without them, we're witnessing the ongoing influence of four lads who, in John's words, were simply "knocking out a bit of work."

The Vee-Jay Records story adds another dimension to this narrative of influence and inspiration. Here was a pioneering Black-owned label that recognised the Beatles' potential a full year before Beatlemania properly erupted, only to be crushed by the legal machinery of a major corporation despite being entirely in the right. Barbara Gardner's trip to London in January 1963 to secure the Beatles licensing deal shows remarkable foresight - or perhaps it was simply good business instinct recognising quality when it heard it.

The fact that Vee-Jay managed to shift 2.6 million Beatles singles in a single month speaks to both the power of the music and the tragic irony of American capitalism - the label's success with the Beatles ultimately contributed to its downfall. "The growth was just too fast," Calvin Carter recalled, a sentiment that could serve as an epitaph for many a music business casualty.

Meanwhile, the White Album continues to yield fresh insights sixty years after its creation. The revelation that several songs were inspired by real people encountered during the Beatles' Indian sojourn - "Dear Prudence" about Prudence Farrow's tent-bound meditation, "Sexy Sadie" originally titled "Maharishi" - reminds us that even the most psychedelic Beatles material often had prosaic roots.

The album sessions also marked the beginning of the end, with Ringo's brief departure serving as a harbinger of the fractures to come. That Paul stepped in to play drums on "Back in the USSR" and "Dear Prudence" whilst Ringo was off on his boating holiday adds poignancy to the tale - here was the most diplomatic Beatle literally keeping the beat whilst the band began to fall apart around him.

All of this Beatles business rumbles on, seemingly impervious to the passage of time, changes in musical fashion, or the steady march of mortality. They remain, as John once noted with typical irreverence, "just a con job" - except it's a con job that's lasted longer than most governments and shows no signs of losing its potency.

The current chart resurgence of "From Us to You" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" suggests that reports of physical media's death have been greatly exaggerated, at least where the Beatles are concerned. In an age of algorithmic playlists and streaming services, there's something almost quaint about people actually purchasing records - as if the act of ownership still matters when the music itself has achieved a sort of cultural omnipresence.

Perhaps that's the real measure of the Beatles' achievement: not just that they made great music, but that they created something so durable, so endlessly fascinating, that even their critics become part of the story. Lyndon Whittaker's 1962 review may have missed the mark, but in doing so, he became part of Beatles lore - which is probably more immortality than most of us can hope for. And really, in a world where everyone's a critic and opinions flow like water, there's something rather charming about a journalist who was brave enough to call it as he heard it, even when history would prove him spectacularly wrong.

Supposedly, Coming Up inspired Lennon to return to the recording studio. If so, it's rather surprising, given the unexciting performance on the minimalist McCartney II. It really stood our in live performances.