REVEALED: The Brutal Truth About John Lennon's Secret Hatred of "Maxwell's Silver Hammer"

How a Radio Luxembourg interview exposed the cracks that would shatter the Fab Four just months later

John Lennon dismissed Paul's "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" as merely "a typical McCartney singalong"

Lennon praised George Harrison's contributions, calling "Something" the best track on the album

The Abbey Road medley was revealed to be a convenient "way of getting rid of bits of songs" the band couldn't be bothered to finish

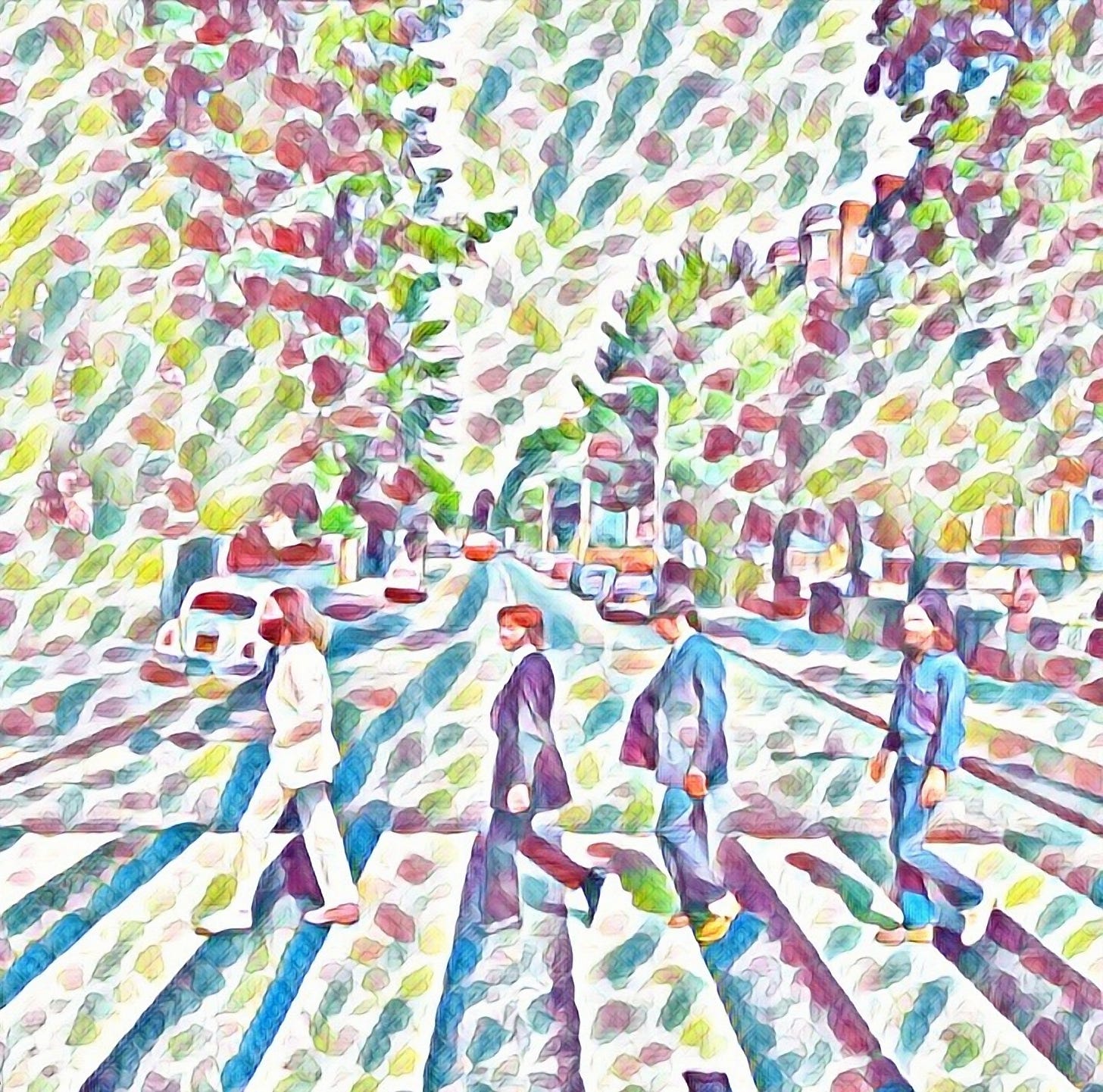

When I first heard Abbey Road in September 1969, I was queuing outside my local record shop in Tooting, clutching my pocket money in sweaty palms, desperate to get my hands on what rumours suggested might be the last Beatles album ever. As I slid the pristine vinyl from its sleeve, admiring the now-iconic zebra crossing photograph, little did I know that John Lennon had already been spilling the beans about the album's creation to Radio Luxembourg, revealing the tensions and frustrations that would soon tear the group apart for good.

This candid interview with Tony McCarthur, unearthed and examined all these years later, shows a refreshingly honest Lennon dissecting the album track by track, offering unvarnished opinions that would make the band's press officer faint into his cup of Earl Grey. It's a fascinating glimpse into Lennon's mind, recorded at a time when the band was held together with little more than Sellotape and Paul McCartney's dogged determination.

"I think it's pretty funky," Lennon said of his own contribution, "Come Together," with his characteristic mixture of self-deprecation and swagger. "I'm biased because it's my song but I dig it." What's more revealing, however, is his immediate pivot to praise George Harrison's "Something," calling it "the best track on the album." This from a man who, alongside McCartney, had dominated Beatles songwriting since the band's inception! The times, they were a-changin' (sorry, wrong artist).

The interview becomes particularly juicy when Lennon discusses "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," McCartney's jaunty tune about a serial killer with a penchant for cranial trauma. Lennon describes it semi-scathingly as "a typical McCartney singalong," before revealing that Paul "really drived [sic] George and Ringo into the ground recording it." One can almost hear Lennon's eyes rolling as he delivers this assessment. Tellingly, this was the only track on the album on which Lennon played no part whatsoever, having been recuperating from a car accident during its recording – or so he claimed. Perhaps he was simply in his own "Nowhere Man" phase, choosing to abstain rather than play another chirpy McCartney ditty.

When discussing Ringo's sole contribution, "Octopus's Garden," Lennon is politely encouraging in the manner of a parent praising a child's finger painting. He explains that the song is about "being at the bottom of the sea and getting away from it all" – a sentiment that Ringo, perpetually overshadowed by his bandmates, might have found particularly appealing. Lennon adds that "it'll be a few years before his production is going as fast as ours, it took George a few years." Before sardonically adding: "It's a Singalong Singalong song." One wonders if Lennon ever considered that perhaps Ringo wasn't writing more songs because his contributions were regularly met with such faint praise.

The interview takes a particularly illuminating turn when discussing the album's famous medley – that 16-minute suite of song fragments that concludes the album. Rather than the work of genius many critics have since proclaimed it to be, Lennon reveals it was simply a convenient "way of getting rid of bits of songs that we'd had for years." He even admits that "George and Ringo wrote bits of it literally in between breaks as we did it" and that "Paul would say we've got 12 bars here so let's fill it in, so we'd fill it in on the spot." So much for the grand artistic vision! It seems the medley was less a carefully orchestrated farewell symphony and more a clearout of the Beatles' musical attic.

Of his own contribution "Sun King," Lennon candidly admits, "It was just half a song I had that I never finished so it was just a way of getting rid of it without ever finishing it." Imagine saying that about what critics would later analyse as a profound artistic statement! It's rather like Michelangelo confessing that he only painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling because he had some paint left over from decorating his kitchen.

The admission about "Mean Mr Mustard" and "Polythene Pam" is equally revealing. Lennon explains that in "Mr Mustard," he originally mentioned a sister named Shirley, but changed it to Pam "to make it sound like it had something to do with" the song "Polythene Pam." As he puts it, they "just juggled them about so they made vague sense." The seemingly interconnected narrative of the medley was, it seems, "just luck." One in a million, you might say.

Abbey Road was released during a particularly fraught period for the Beatles. While the "Let It Be" sessions earlier that year had been so tense and miserable that the recordings were temporarily shelved (they would later be released as the band's final album, despite Abbey Road being recorded after them), Abbey Road represented a last-ditch attempt to make a proper Beatles album. Producer George Martin had persuaded the band to "let's get back to making a record like we used to," and the result was an album that, despite the internal tensions, showcased each Beatle's distinctive talents.

What's particularly striking about Lennon's Radio Luxembourg interview is how generous he is about Harrison's contributions. At a time when Harrison was increasingly frustrated at being sidelined by the Lennon-McCartney partnership, Lennon's praise for "Something" and "Here Comes The Sun" seems genuine. He notes that Harrison's "Here Comes The Sun" reminds him of Buddy Holly and observes that "once the floodgates have now opened it becomes an effort to concentrate on writing certain types of songs." This inadvertently highlighted the problem: Harrison's songwriting had matured to the point where the confines of the Beatles could no longer contain it. All those guitar licks would soon be "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" no more.

The Moog synthesizer makes a notable appearance on "I Want You (She's So Heavy)," with Lennon explaining that "the Moog synthesizer can do all sound, all ranges of sound, so we did that on the end and if you're a dog you'll hear a lot more." One wonders if EMI considered marketing the album to canines – perhaps they could have called it "It's Been a Hard Day's Night... For Dogs."

Lennon's description of the genesis of "Because" reveals a touching musical interaction with Yoko Ono, whose presence in the studio had become a point of contention with the other Beatles. "Yoko plays classical piano and she was playing one day and I don't know what she was playing, I think it was Beethoven or something so I said give me those chords backwards." It's a tender glimpse of the musical relationship between Lennon and Ono, who by this point had become inseparable – much to the chagrin of the other Beatles, who found themselves with an unexpected fifth wheel in the studio.

What's conspicuously absent from Lennon's track-by-track analysis is any mention of "The End," with its famous line "And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make." Perhaps Lennon found this McCartney sentiment too saccharine for his acerbic tastes, preferring to let his own more cynical worldview shine through. After all, this was the man who would later write "God is a concept by which we measure our pain" and declare "The dream is over."

At the time of Abbey Road's release, the Beatles were already functionally separated. Lennon had privately informed the others that he was leaving the band, though this wouldn't be made public until the following year. McCartney had retreated to his farm in Scotland, Harrison was exploring Indian spirituality and collaborating with other musicians, and Ringo was, well, being Ringo – solid, reliable, and often overlooked.

The critics, unaware of the band's imminent dissolution, largely praised Abbey Road. The New Musical Express called it "another triumphant chapter in the story of the most successful entertainment phenomenon of the 20th century," while Melody Maker declared it "their best album since Sergeant Pepper." Rolling Stone was more measured, noting that "Abbey Road will stand as one of the most interesting Beatles LPs... if not the best Beatles album ever." American critics were particularly enamoured with the medley, with the New York Times describing it as "a series of musical fragments that, when united, form a larger pattern." If only they'd known those fragments were just the band's leftovers, stitched together like an old patchwork quilt!

The album's cover – showing the four Beatles crossing the road outside their recording studio – has become one of the most iconic and parodied images in popular culture. Yet it's also laden with symbolism that fans have spent decades decoding. McCartney is barefoot (he's dead, obviously), Lennon is dressed in white (he's Jesus, obviously), Ringo is in a undertaker's suit (he's... an undertaker, obviously), and Harrison is in denim (he's... a cowboy? Less obvious). The number plate of the Volkswagen Beetle in the background reads "LMW 28IF" – which conspiracy theorists claimed meant "Linda McCartney Weeps" and that Paul would have been 28 IF he had lived. The fact that McCartney was actually 27 at the time didn't deter the theorists. Facts rarely do.

The real symbolism, however, is in the image itself: the Beatles walking away from their studio, moving in the same direction but with clear space between them. Within a year, they would be walking in entirely different directions, pursuing solo careers with varying degrees of success. "I Read the News Today, Oh Boy," indeed.

Abbey Road represented both an ending and a beginning. It was the last album the Beatles recorded together (though not the last they released), and it pointed the way forward for each member's solo career. Lennon's raw, confessional style on "Come Together" would evolve into the stark honesty of "John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band." McCartney's meticulous craftsmanship on tracks like "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" would continue through his work with Wings and beyond. Harrison's blossoming songwriting talent would explode on "All Things Must Pass," while Ringo would... well, Ringo would continue being Ringo, bless him.

What John Lennon's Radio Luxembourg interview reveals is not just his thoughts on Abbey Road, but a band already drifting apart. His praise for Harrison and relative silence on McCartney's contributions speaks volumes. His dismissal of the medley – often considered the album's crowning achievement – as a convenient way to use up song fragments shows a pragmatism at odds with the group's mythical status. And his offhand comments about Ringo's songwriting suggest a hierarchy that had long been established within the band.

Yet despite all this, Abbey Road stands as a remarkable achievement. The band that had revolutionised popular music managed, despite their personal differences, to create one last masterpiece before going their separate ways. As Lennon himself would later sing, "You can go your own way" (oh wait, that was Fleetwood Mac – my mistake).

The album's enduring popularity is testament to its quality. Fifty years after its release, it still sounds fresh and innovative. Each song, from the funky "Come Together" to the tender "Something," from the quirky "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" to the majestic medley, showcases a band at the height of their powers. Even if, as Lennon's interview suggests, they were already eyeing the exit door.

In retrospect, perhaps Abbey Road's most poignant aspect is that it represents the Beatles at their most mature and collaborative. Gone are the Beatlemania days of "She Loves You" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand." Instead, we have four musicians who had grown up together, grown apart, but still managed to come together (right now) one last time to create something timeless.

Lennon's analysis, with its blend of pride, criticism, and indifference, offers a fascinating glimpse into the mind of a man already moving on from the band that had defined his life for a decade. His candid comments about "getting rid of bits of songs" and Paul "driving George and Ringo into the ground" reveal the fraying relationships that would soon snap completely.

The Beatles would never record together again after Abbey Road. The "Let It Be" album, released later, was actually recorded earlier and then shelved due to the band's dissatisfaction with it. By the time Abbey Road hit the shelves, Lennon had already mentally left the band, McCartney was plotting his solo debut, Harrison was writing songs that would form his triple album "All Things Must Pass," and Ringo was... well, Ringo was probably just happy to be there.

The album's final track, "The End," features the only drum solo Ringo ever recorded with the Beatles, followed by a round-robin of guitar solos from McCartney, Harrison, and Lennon. It's a fitting farewell, each Beatle taking a final turn in the spotlight before Paul delivers that famous final line: "And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make." After which, tellingly, comes "Her Majesty," a 23-second afterthought that undermines any sense of grand finale. It's as if the Beatles couldn't resist one last cheeky wink.

John Lennon's track-by-track analysis of Abbey Road, conducted shortly after its release for Radio Luxembourg, offers a uniquely candid insight into the album's creation. Untainted by decades of critical analysis and mythmaking, it shows a band already fragmenting, already looking beyond the Beatles to their individual futures. Yet it also shows a band still capable of creating magic, still able to combine their distinctive talents into something greater than the sum of its parts.

Half a century later, Abbey Road remains a testament to what the Beatles achieved together, even as they were preparing to go their separate ways. As John later sang, "Life is what happens to you while you're busy making other plans." The Beatles were planning their exits, but they still managed to make one hell of an album on their way out the door.

In the immortal words of "The End": "Boy, you're gonna carry that weight a long time." And indeed, the cultural weight of Abbey Road has been carried for over 50 years now, showing no signs of being put down. Not bad for an album that, according to one of its creators, was partly made up of bits of songs they couldn't be bothered to finish properly.

As Peter Cook might have put it in the pages of Private Eye: "The Beatles' final album together – or, as John Lennon might describe it, 'a convenient way of getting rid of bits of songs we'd had for years.' Now available wherever fine records are sold, for only seven shillings and sixpence. Partial songs never sounded so complete!"

Fifty years on, I still have that vinyl I bought in Tooting. The sleeve is worn, the vinyl scratched, but when I put it on the turntable and hear those opening chords of "Come Together," I'm transported back to 1969, to a time when four lads from Liverpool changed the world one song at a time. Even if, as John Lennon revealed, some of those songs were just bits and pieces they were trying to get rid of.

But then again, as John himself might have said: "You know, the Beatles' leftovers were still better than most bands' main courses." And that, dear reader, is the gospel according to John. Or should that be the gospel according to "Cranberry Sauce"?

If you ever watched that Disney + documentary of the making of Let It Be, it’s crystal clear that Harrison’s disgruntlement was pretty much the catalyst to the break up. After watching that, I do think Yoko Ono got a bad rap, even if the other Beatles were not entirely thrilled she was sitting in their sessions. But what’s also very apparent is that McCartney was the driver of the group. Not Lennon/McCartney, just McCartney. He was the taskmaster, the drill sergeant, and the one keeping the trains running on time. Lennon wasn’t disciplined enough and/or he was already mentally checked out. The others resented Paul for this, but I found it pretty enlightening that Lennon was always considered the artistic genius, but Paul’s musical range was amazing. Anyway, what really stuns me to this day is how young they all were when they were cranking out album after album. Honestly, they were all burned out, the chinks in their relationships notwithstanding.

Side 2 of Abbey Road was genius. If it’s true that it was just put together on the spot, that only makes it more brilliant.