From Quarry Bank to Eternity: John Lennon's Rebellious Education

How a Liverpool schoolboy's cheeky insolence shaped music history

John Lennon's formative years at Quarry Bank High School revealed a pattern of brilliant rebellion that would later define The Beatles' revolutionary approach to music and culture

His early artistic tendencies faced institutional discouragement, pushing him toward the anti-establishment attitude that became central to his creative identity

Lennon's unique humour, influenced by The Goon Show, Scouse wit, and absurdist comedy, became a cornerstone of The Beatles' appeal and a shield against the madness of fame

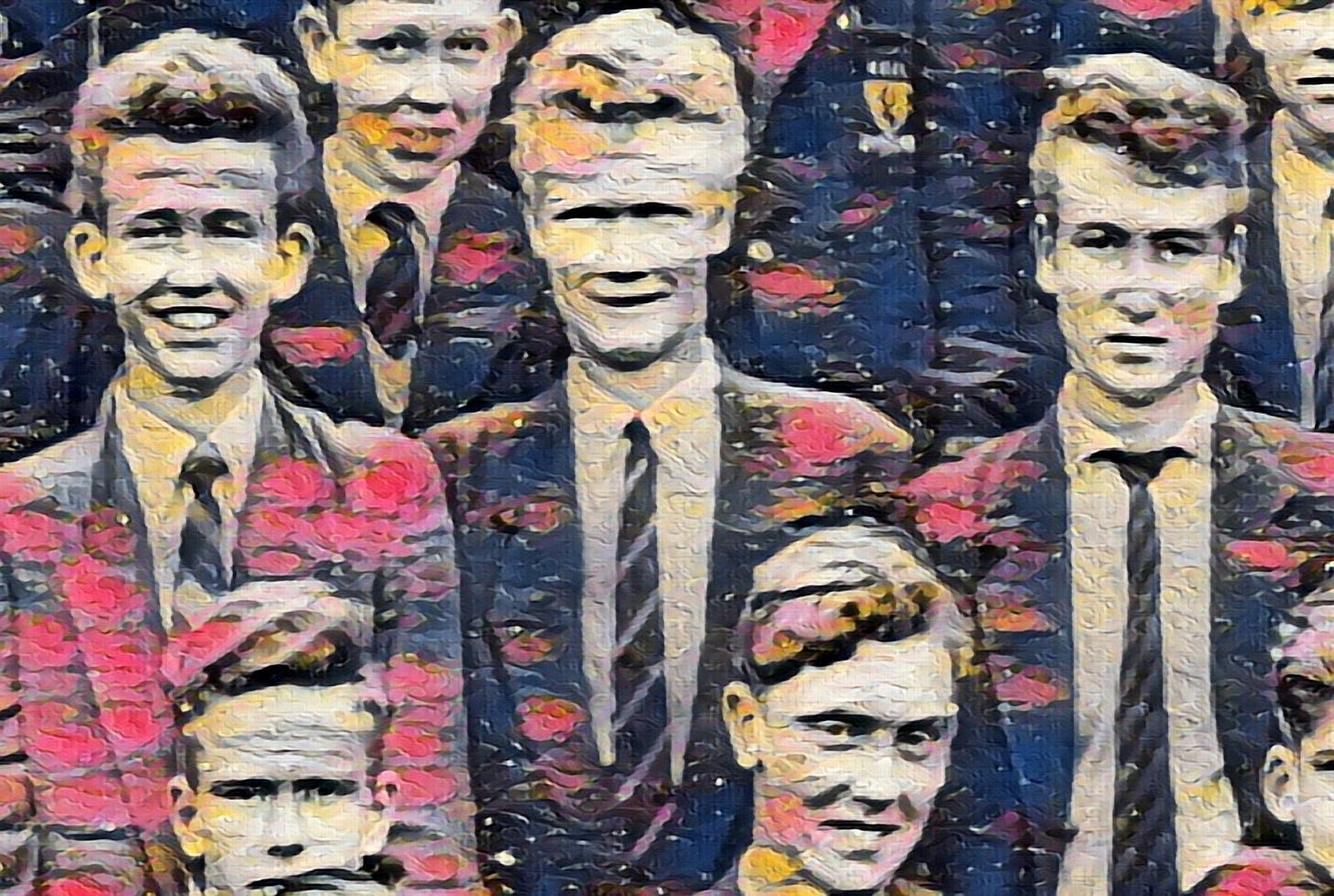

Many a revolution has started in the classroom, though few teachers would care to admit it. In John Lennon's case, the halls of Liverpool's Quarry Bank High School in the 1950s might well have been the unlikely incubator for what would eventually become the most significant cultural earthquake of the 20th century. The evidence has long been hiding in plain sight—in school reports declaring him "on the road to failure," in detention slips for "disruption," and in the margins of school notebooks filled with surrealist sketches and absurdist wordplay.

"When I was fifteen I was thinking, 'If only I can get out of Liverpool and be famous and rich, wouldn't it be great?'" Lennon later reflected. It's a sentiment shared by countless teenagers throughout history, but few managed to manifest such ambitions with quite the same spectacular results. Fewer still would so thoroughly transform the cultural landscape in the process.

The schoolboy Lennon was, by his own admission, a study in contradictions. "I was aggressive because I wanted to be popular. I wanted to be the leader," he confessed. "It seemed more attractive than just being one of the toffees." This blend of insecurity and ambition would later fuel both his creative brilliance and personal demons. Lennon's early education at Dovedale Infants School had been relatively uneventful, but by the time he arrived at Quarry Bank—one of Liverpool's more prestigious grammar schools, which required passing the dreaded "eleven-plus" examination—a pattern of academic underachievement and creative rebellion had firmly established itself.

His aunt Mimi Smith, who raised him after his mother Julia's departure, had deliberately chosen Quarry Bank over the equally prestigious Liverpool Institute (later attended by Paul McCartney and George Harrison) because her brother-in-law taught at the latter. With remarkable foresight, she worried that John might cause family friction with his rebellious tendencies. Her concerns weren't unfounded—Lennon would later name his first skiffle group "The Quarrymen" after the school, perhaps his only sincere tribute to an institution he largely detested.

"Most of the masters hated me like shit," Lennon recalled with characteristic bluntness. "I always wondered, 'Why has no one discovered me?' In school, didn't they see that I'm cleverer than anybody in this school?" This wasn't mere adolescent hubris. Behind the failing grades and disciplinary problems was a genuinely creative mind struggling against the confines of post-war British education.

One need look no further than the infamous "Daily Howl," Lennon's handmade school newspaper filled with surrealist doodles, absurdist stories, and satirical advertisements. "I would write it at night, then take it into school and read it aloud to my friends," Lennon explained. The Daily Howl was Lennon's private rebellion, a creative outlet that foreshadowed both his later published works like "In His Own Write" and the surrealist wordplay that would appear in Beatles songs like "I Am the Walrus."

If you're looking for the roots of Lennon's distinctive humour—that peculiar blend of Scouse wit, absurdist non-sequiturs, and cutting sarcasm—you'll find it developed as a survival mechanism during these school years. Lennon's particular brand of comedy didn't emerge fully formed from the ether; it was nurtured by influences like The Goon Show, which featured the anarchic talents of Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe. As Lennon himself later wrote in a review of Milligan's work, The Goon Show was "the only proof that the world was insane." High praise indeed from a man who would later channel similar absurdist energies into his own artistic expression.

"I suppose I did have a cruel humour," Lennon admitted. "It was at school that it first started." This edge, which could sometimes cut too deeply, was part self-protection and part natural inclination. The sardonic wit that would later charm and occasionally confound journalists at Beatles press conferences was forged in the crucible of Liverpool schoolyard politics, where cleverness with words could compensate for physical vulnerability.

Pete Shotton, Lennon's childhood best friend and fellow Quarry Bank pupil, recalled being known at school as "Shennon and Lotton" or "Lotton and Shennon" due to their shared penchant for mischief. Shotton would briefly join Lennon's Quarrymen as a washboard player before Paul McCartney's arrival prompted a reconsideration of the band's musical direction. The two remained close even after The Beatles achieved worldwide fame, with Lennon later buying Shotton a supermarket on Hayling Island and appointing him manager of Apple Boutique during the band's business ventures.

What's particularly fascinating about Lennon's education—or lack thereof, as he might have put it—was how it shaped his complicated relationship with authority. "I was a particularly offensive schoolboy," Lennon reflected. "I am one of your typical working-class heroes. Mine was the same sort of revolution as D.H. Lawrence's—I didn't believe in class and the whole fight was against class structure."

Yet as with many rebellions, this one contained its contradictions. The same Lennon who claimed to reject the class system had been admitted to one of Liverpool's top grammar schools, and despite his academic failings, later attended Liverpool College of Art—hardly the typical trajectory for a working-class Liverpudlian in the 1950s. His path through these institutions was chaotic and ultimately incomplete, but they nevertheless provided him with cultural exposure and social connections that would prove invaluable.

"If I look through my report card, it's the same thing: 'Too content to get a cheap laugh' or 'Daydreaming his life away,'" Lennon noted. The teachers' assessments weren't entirely wrong. He was indeed pursuing cheap laughs and indulging in daydreams—activities that would eventually prove more lucrative than any conventional career path they might have envisioned for him.

The teachers who dismissed Lennon's potential couldn't have known that his apparent deficiencies—his disregard for authority, his wordplay and wit, his refusal to conform—would become his greatest assets. "One maths master wrote, 'He's on the road to failure if he carries on this way,'" Lennon recalled with evident satisfaction. "Most of them disliked me, so I'm always glad to remind them of the incredible awareness they had."

What those teachers failed to recognise was that Lennon wasn't merely being difficult for difficulty's sake. Beneath the rebellious exterior was a deeply creative soul struggling to express itself through available channels. "All kids draw and write poetry and everything, and some of us last until we're about eighteen, but most drop off at about twelve when some guy comes up and says, 'You're no good,'" Lennon observed. "That's all we get told all our lives: 'You haven't got the ability. You're a cobbler.' It happened to all of us, but if somebody had told me all my life, 'Yeah, you're a great artist,' I would have been a more secure person."

This observation reveals much about Lennon's inner landscape—the insecurity that drove him to act out, the yearning for validation that he masked with bravado. It also suggests a deeper understanding of how educational systems can fail creative children, a theme he would return to in later life with songs like "Working Class Hero."

There was a lifeline, however small, in the form of art classes. "There was always one teacher in each school, usually an art teacher or English language or literature," Lennon acknowledged. "If it was anything to do with art or writing, I was OK, but if it was anything to do with science or maths, I couldn't get it in." Even here, though, Lennon felt the constraints of institutional thinking. "At school we used to draw a lot and pass it round. We had blind dogs leading ordinary people around," he recalled, a description that manages to be simultaneously darkly comic and revealing of his early provocative artistic sensibilities.

The educational system's emphasis on science and practical subjects in the post-war era further alienated the artistically inclined Lennon. "They only wanted scientists in the Fifties," he observed. "Any artsy-fartsy people were spies. They still are, in society." This suspicion of artistic types was particularly pronounced in working-class Liverpool, where practical skills were valued over creative pursuits. "When they ask you, 'What do you want to be?' I would say, 'Well, a journalist,'" Lennon recalled. "I never would dare to say, 'An artist,' because in the social background that I came from—as I used to say to my auntie—you read about artists and you worship them in museums, but you don't want them living around the house."

Even at Liverpool College of Art, which he attended after leaving Quarry Bank, Lennon found the institution attempting to channel his creativity into respectable avenues. "Even at art school they tried to turn me into a teacher—they try to discourage you from painting—and said, 'Why not be a teacher? Then you can paint on Sunday?'" The suggestion that art should be relegated to a hobby rather than a vocation must have seemed particularly insulting to someone who would later describe himself as "a poet"—and who would, ironically, become one of the most commercially successful artists of all time.

Lennon's school years were also marked by his discovery of rock and roll, a revelation that would ultimately provide him with an escape route from the conventional paths that seemed to be closing in around him. By 1956, while still at Quarry Bank, he had formed the Quarrymen, initially a skiffle group inspired by Lonnie Donegan's hit version of "Rock Island Line." The group went through various incarnations before its fateful encounter with Paul McCartney at the Woolton Parish Church garden fête in July 1957, the meeting that would eventually transform them into The Beatles.

This transition from schoolboy rebel to cultural revolutionary wasn't immediate, of course. After leaving Quarry Bank, Lennon's brief time at Liverpool College of Art overlapped with the early days of The Beatles, as the band developed from a schoolboy skiffle group into a leather-clad rock and roll outfit playing Hamburg clubs. His dual identity as art student and musician eventually resolved itself when the band's success made further education unnecessary.

The influence of Lennon's educational experiences—both what he learned and what he rejected—can be traced throughout his career with The Beatles and beyond. The wordplay and surrealism of his school writings evolved into the lyrics of songs like "I Am the Walrus" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds." The distrust of authority fostered in school classrooms manifested in the band's increasingly political stance and Lennon's later peace activism. Even his famous wit, displayed in countless press conferences and interviews, had its genesis in those schoolyard exchanges where a sharp tongue could deflect unwanted attention.

Perhaps most significantly, Lennon's educational experiences reinforced his outsider status—a position that, paradoxically, would help him connect with millions. He was the misfit who made misfits feel seen, the rebel whose rejection of convention gave others permission to question the status quo. His school days might have been marked by conflict and underachievement, but they helped shape the artist who would later write "Imagine," a song that asks listeners to envision a world without divisions or hierarchies.

In a famous 1970 interview, Lennon proclaimed, "I wasn't a working-class hero... I was a working-class hero who remained working class and became a millionaire. That's a contradiction in terms, isn't it?" This kind of self-aware contradiction had been present since his school days, when the rebellious student who rejected educational authority nevertheless craved recognition for his intelligence and creativity.

Lennon's relationship with Quarry Bank High School remained complicated even after his fame eclipsed anything his teachers might have predicted. According to contemporaries, as The Beatles rose to global prominence in the mid-1960s, mentions of Lennon by teachers at the school decreased—even as unauthorized carvings of his name in wooden desks multiplied. It was as if the institution couldn't quite reconcile its most famous alumnus with its own self-image.

Today, Quarry Bank High School no longer exists under that name, having merged with other local schools in 1967 to become Quarry Bank Comprehensive School, and later Calderstones School in 1985. Yet its most famous pupil's legacy endures far beyond educational reorganisations and renamed institutions. Lennon's journey from troublesome schoolboy to cultural icon serves as both inspiration and cautionary tale—a reminder that our educational systems often fail to recognise or nurture the very talent that might transform our world.

As for Lennon himself, perhaps his most revealing comment about his education came when he reflected on what might have been: "When I was about twelve, I used to think I must be a genius but nobody'd noticed. I thought, 'I'm a genius or I'm mad. Which is it? I can't be mad because nobody's put me away—therefore I'm a genius.'" With characteristic wit, he added, "I mean, a genius is a form of mad person. We're all that way, but I used to be a bit coy about it—like my guitar-playing. If there's such a thing as genius, I am one. And if there isn't, I don't care. I used to think it when I was a kid writing my poetry and doing my paintings."

The schoolboy who once filled notebooks with surreal drawings and wordplay, who infuriated teachers with his disruptive behaviour, who dreamed of escape from Liverpool, would ultimately find vindication beyond anything he could have imagined. The same qualities that made him a problematic pupil—his irreverence, his creativity, his questioning of authority—would make him an icon. Lennon's education, in the end, wasn't found in the classrooms of Quarry Bank, but in his restless journey beyond them. As he himself put it with typical Scouse understatement, "Genius is pain, too. It's just pain."

In the halls of Quarry Bank, where teachers once predicted failure for their rebellious charge, the echo of "Imagine" now resonates more loudly than any headmaster's reprimand. John Lennon may have been a terrible student, but he turned out to be one hell of a teacher.

Interesting article. Thanks. Still, I am not convinced that he was that working class. His aunt and uncle were middle class (in an interview on YouTube her accent sounds a bit like the Queens’s) and many people have been reported saying that he forced his Liverpool accent. The true working class Beatles were Ringo and George, whom Lennon’s aunt used to snub a lot (according to George) because of his working class origin and very strong accent.