March 1st, 1975

The morning dawned with the inevitability of yet another Saturday, one seemingly unremarkable day in the grand cosmic joke we call life. But for those of us who've spent the better part of a decade tracking the movements of Liverpool's fab fugitives like obsessive ornithologists, March 1st, 1975 offered a rare glimpse of John Winston Ono Lennon in his natural habitat: causing mischief on live television.

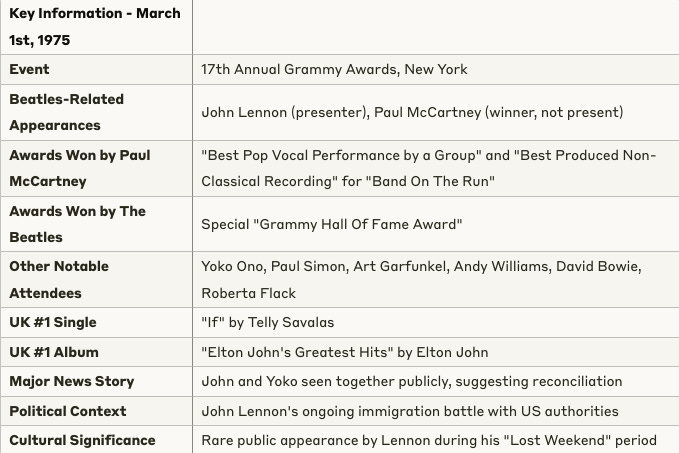

There he stood on the Grammy Awards stage in New York City, bedecked in his trademark beige cap and scarf—looking like a revolutionary disguised as a taxi driver—about to present an award with the unlikely companions of Paul Simon and Andy Williams. The blind date from hell, or perhaps heaven, depending on your perspective. The establishment's crooner, the poet of Central Park, and the acid-tongued Beatle forming a temporary trio that nobody had requested, but everybody suddenly needed.

"SHALL WE GET ON WITH IT? MY GOD, SO THIS IS WHAT DAWN DOES, IS IT?"

The night was already a carnival of surrealism before Lennon approached the microphone. As the television cameras panned to the audience, there sat Yoko Ono in the front row, sphinx-like and watchful, a living embodiment of avant-garde vigilance in a sea of industry suits and sequins. The reunited couple's appearance together was itself a revelation, like spotting twin unicorns grazing casually in Central Park.

When John stepped onto the podium with Simon and Williams, what unfolded wasn't just an award presentation but an impromptu comedy routine that dripped with the particular brand of sardonic humour that has made Lennon both revered and feared since his moptop days.

"Hello, I'm John. I used to play with my partner Paul," Lennon announced, his Liverpudlian inflection cutting through the polished American atmosphere like a rusty hacksaw.

Simon, picking up the thread: "I'm Paul. I used to play with my partner Art."

Not to be outdone, Williams added: "I'm Andy. I used to play with my partner Claudine."

The audience roared at this reference to Williams' messy split from his wife Claudine Longet. It was the kind of moment television executives simultaneously dread and pray for—unscripted, slightly uncomfortable, utterly compelling.

Williams, apparently emboldened by the laughter, continued his confessional comedy by telling John and Paul that their music had "helped tell the story" of his relationship: "It started off with 'I Want To Hold Your Hand' and finished off with 'Bridge Over Troubled Water'."

"Touching, touching," replied Lennon with the deadpan delivery of a mortician announcing lunch.

There was something deliciously perverse about watching John Lennon—the man who once claimed the Beatles were more popular than Jesus—participating in the ritualistic backslapping of the American music industry. This was, after all, the same John Lennon who had spent the better part of four years fighting deportation from the United States, a battle that according to that day's Melody Maker would "reach a climax within the next three months."

THE SURREAL BECOMES EVEN MORE UNHINGED

As if the cultural cocktail wasn't already potent enough, Art Garfunkel himself emerged from the audience to accept an award on behalf of Olivia Newton-John. Suddenly, the stage became a miniature reunion of broken partnerships, a Mount Rushmore of musical divorce.

Lennon, never one to let a moment of potential discomfort pass unmolested, introduced Simon to Garfunkel as if they were strangers, adding the perfectly timed: "Which one of you is Ringo?"

Then came the inevitable question, the one that follows broken musical partnerships like shadows: "Are you ever getting back together again?" Lennon asked the Simon & Garfunkel duo.

Simon, quick on his feet, parried: "Are you guys getting back together again?"

"It's terrible, isn't it?" sighed Lennon, in a moment of genuine reflection amid the comedy. The weight of a thousand interview questions seemed to hang in that sigh, the collective yearning of millions for the impossible return of the Beatles condensed into three words and an exhalation.

Garfunkel, apparently missing the memo about keeping things light, leaned into the microphone and asked Simon: "Are you still writing?"

"I'm trying my hand at a little acting, Art," replied Simon.

Lennon, perhaps sensing the conversation drifting toward substantive territory, brought things firmly back to absurdity by asking: "Where's Linda?" When the joke failed to land, he added with perfect self-awareness: "Oh well, too subtle that one." After Garfunkel's serious acceptance speech, Lennon couldn't resist a final jab: "You're so serious."

MACCA'S SILVERWARE AND THE BEATLES' LEGACY

While John was busy creating chaos on stage, his former writing partner was quietly accumulating more hardware for his mantelpiece. Paul McCartney won two Grammy Awards that night for his Wings album "Band On The Run"—"Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Group" and "Best Produced Non-Classical Recording."

These wins represented a significant moment in McCartney's post-Beatles career. "Band On The Run" had been recorded under difficult circumstances in Lagos, Nigeria, after two members of Wings quit just before the sessions began. That it went on to become not just a commercial success but a critical one as well was a vindication for McCartney, who had endured years of critical drubbings while Lennon was hailed as the "artistic" ex-Beatle.

The Beatles themselves received a special "Grammy Hall Of Fame Award" that night, a bittersweet recognition of a band that now existed only in memory and on vinyl. The group had a complicated history with the Grammy Awards during their active years. Despite revolutionising popular music in the 1960s, they had won relatively few Grammys while together.

Their first Grammy came in 1965, when they won Best New Artist and Best Performance by a Vocal Group for "A Hard Day's Night." The following year, they won Best Contemporary Album for "Help!" In 1968, they won Album of the Year for "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" and Best Contemporary Album for the same record. "Michelle" won Song of the Year in 1967, and "Hey Jude" won Record of the Year in 1969.

But many of their most innovative works—"Revolver," "The White Album," "Abbey Road"—went unrecognized by the Recording Academy at the time of their release, an oversight that makes their Hall of Fame induction seem both overdue and inadequate.

THE REUNION THAT MADE HEADLINES

After the ceremony, Lennon attended an after-show party with other luminaries including Roberta Flack and David Bowie. But it wasn't his mingling with other musicians that caught the attention of the press. It was the fact that Yoko Ono was seen chatting with him backstage and later photographed leaving the event with him.

This seemingly mundane detail made the front page of the Daily Mirror back in England on Monday, March 3rd. To understand why, one must recall that John and Yoko had separated in the summer of 1973, when Lennon embarked on his infamous "Lost Weekend"—a misnomer if ever there was one, as this "weekend" lasted 18 months and involved a very public relationship with May Pang, Yoko's former assistant.

During this period, Lennon had been living in Los Angeles, indulging in epic bouts of drinking with companions like Harry Nilsson, Ringo Starr, and Keith Moon—a triumvirate guaranteed to lead even the most disciplined soul astray. His behaviour during this time became legendary: getting thrown out of the Troubadour Club for heckling the Smothers Brothers with a sanitary napkin on his head, producing Nilsson's "Pussy Cats" album during marathon recording sessions fuelled by brandy and cocaine, and generally embracing the kind of rock star excess he had previously satirised.

So, the sight of John and Yoko together again was significant. It suggested a reconciliation, a homecoming, a restoration of order to a narrative that had spun wildly off course. It was, in its way, as much a reunion as fans could hope for in 1975, when a Beatles reformation seemed about as likely as Richard Nixon winning a Nobel Peace Prize.

THE FIGHT TO STAY IN AMERICA

Meanwhile, as John was presenting awards and reuniting with Yoko, a battle was raging behind the scenes—one that could potentially see him forcibly removed from his adopted home. The Melody Maker that day carried a story entitled "John's No.1 Dream," detailing his ongoing immigration struggle.

His lawyer, Leon Wildes, claimed to have evidence that the government was deliberately obstructing Lennon's application to remain in the United States. According to Wildes, a memorandum had been circulated instructing government agencies to keep John and Yoko "under physical observance at all times because of possible political activities."

The Nixon administration had been determined to deport Lennon, viewing him as a dangerous radical whose influence could mobilise the youth vote against the president in the 1972 election. That Nixon was now disgraced and removed from office while Lennon remained in New York was a irony surely not lost on the ex-Beatle.

Wildes stated that if he could find the source of this mysterious document, it would "break the case wide open and prove that there has been a miscarriage of justice." The lawyer's confidence would prove prophetic—Lennon would eventually receive his green card in July 1976, after years of legal battles.

THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF MARCH 1ST, 1975

As John Lennon was jesting on the Grammy stage in New York, back in the UK, the cultural landscape was in a state of fascinating flux. The mid-70s represented a hinge moment in British popular culture, with glam rock fading, punk still percolating beneath the surface, and disco beginning its ascendancy.

On the UK singles chart, Telly Savalas' spoken-word version of "If" inexplicably clung to the number one position—proof, if any were needed, that the public's taste remains forever inscrutable. The charts also featured "Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)" by Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel, "January" by Pilot, and "Black Superman (Muhammad Ali)" by Johnny Wakelin & the Kinshasa Band.

On the album charts, Elton John's "Greatest Hits" compilation was at number one, with "Physical Graffiti" by Led Zeppelin—just released the previous week—already climbing rapidly. "Crime of the Century" by Supertramp and "Blood on the Tracks" by Bob Dylan were also selling well, indications that the album-oriented rock that the Beatles had pioneered with "Sgt. Pepper" continued to dominate the market.

British television that Saturday evening offered a cultural snapshot of a nation in transition. BBC1 featured "Jim'll Fix It," where Jimmy Savile granted wishes to children (a programme that has since taken on far darker connotations), followed by "The Generation Game" with Bruce Forsyth. On BBC2, viewers could watch "Westminster" for political analysis, while ITV offered "Celebrity Squares" and "Within These Walls," a drama set in a women's prison.

Radio 1's daytime programming was still dominated by the relentlessly cheerful Tony Blackburn and the more acerbic Noel Edmonds, while the evening brought John Peel's influential show, championing new and underground music with the same passion he had shown when playing The Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows" back in 1966.

JOHN LENNON: GRAMMY PRESENTER EXTRAORDINAIRE?

The Grammy Awards appearance represented something of an anomaly in Lennon's post-Beatles career. He was not, generally speaking, one for industry events. His appearance at the 1975 ceremony marked his first time as a presenter at a major awards show.

The Beatles themselves had rarely attended award ceremonies during their active years. They famously didn't turn up to collect their Grammy Awards in person, being somewhat ambivalent about such recognition and, in their later years, too busy reinventing popular music to bother with acceptance speeches.

Lennon's comfort level on the Grammy stage was hard to gauge. On one hand, he seemed to relish the opportunity for mischief-making, for puncturing the pomposity of the occasion with his barbed wit. On the other, there was a palpable nervous energy to his performance, a sense that he was simultaneously embracing and mocking the role of celebrity presenter.

What was clear, however, was that he hadn't lost his ability to command attention. Even in a room full of the biggest stars in the music industry, all eyes and ears were on Lennon. His charisma remained undiminished by years of relative seclusion and personal turmoil.

Perhaps most significantly, his appearance represented a tentative re-engagement with the public world. After the dissolution of the Beatles and the sometimes painfully confessional nature of his solo albums "John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band" and "Imagine," Lennon had retreated somewhat from public view. His immigration troubles had further complicated his relationship with fame and visibility.

So, to see him on stage, trading quips with Paul Simon and Andy Williams, was to witness a man cautiously re-emerging from a period of darkness. The fact that he was there with Yoko, that they were together again, added another layer of significance to the appearance.

THE AFTERMATH AND WHAT CAME NEXT

In the days and weeks following his Grammy appearance, Lennon would continue his process of reconciliation—with Yoko, with his past, and eventually with his creativity. By the end of 1975, he and Yoko would release the compilation album "Shaved Fish," and Lennon would embark on what he later called his "househusband" period, stepping back from music to focus on raising his son Sean, born on October 9th, 1975 (coincidentally, John's 35th birthday).

Meanwhile, McCartney and Wings would build on the success of "Band On The Run" with the release of "Venus and Mars" in May 1975, followed by a world tour. George Harrison would continue to release solo albums and, in 1976, would face a lawsuit alleging that "My Sweet Lord" plagiarised the Chiffons' "He's So Fine." Ringo Starr would carry on with his solo career, achieving varying degrees of success.

The Beatles as a unit remained firmly in the past, despite persistent rumours of reunions and astronomical financial offers. The closest fans would get in 1975 was seeing John Lennon and Paul Simon joking about their former partners on the Grammy stage—a bittersweet reminder of what was lost and what might have been.

On that March evening in 1975, as John Lennon walked through the New York night with Yoko Ono by his side, perhaps he felt something like contentment. His "Lost Weekend" was over. He was home.

The writer is now going for a drink. Or several. When the music's this good and the nostalgia this potent, sobriety seems a waste of a perfectly good nervous system.