February 4, 1972

There's a peculiar irony in watching the greatest democracy in the world attempt to silence a pop star. But here we are, on this grey February morning in 1972, and some stuffed shirt in Washington is typing out a memo suggesting that John Lennon – yes, that John Lennon – should be given the old heave-ho from the Land of the Free. The whole thing reeks of paranoia, wrapped in bureaucracy, served with a side of political manipulation.

I'm sitting here in my flat in Primrose Hill, looking out at the drizzle while Radio 1's Tony Blackburn chirps away about some new David Cassidy single, and I can't help but think about the absurdity of it all. Our John, the mouthy git from Liverpool who once told us to imagine there's no countries, is now being branded an "undesirable alien" by the very country that made him a millionaire several times over.

The memo, penned by Senator Strom Thurmond to Attorney General John Mitchell, reads like something straight out of a bad spy novel. "Undesirable alien," they call him. Funny that – I remember when the only undesirable thing about John was his tendency to wear those bloody awful granny glasses.

But let's rewind the tape a bit, shall we? How did we get here? It's been just over two years since the Beatles gave their final bow, leaving us all with "The Long and Winding Road" still echoing in our ears. John had already gone off on his own tangent, screaming his lungs out with the Plastic Ono Band and telling us that the dream was over. But it wasn't just about the music anymore – it hadn't been for quite some time.

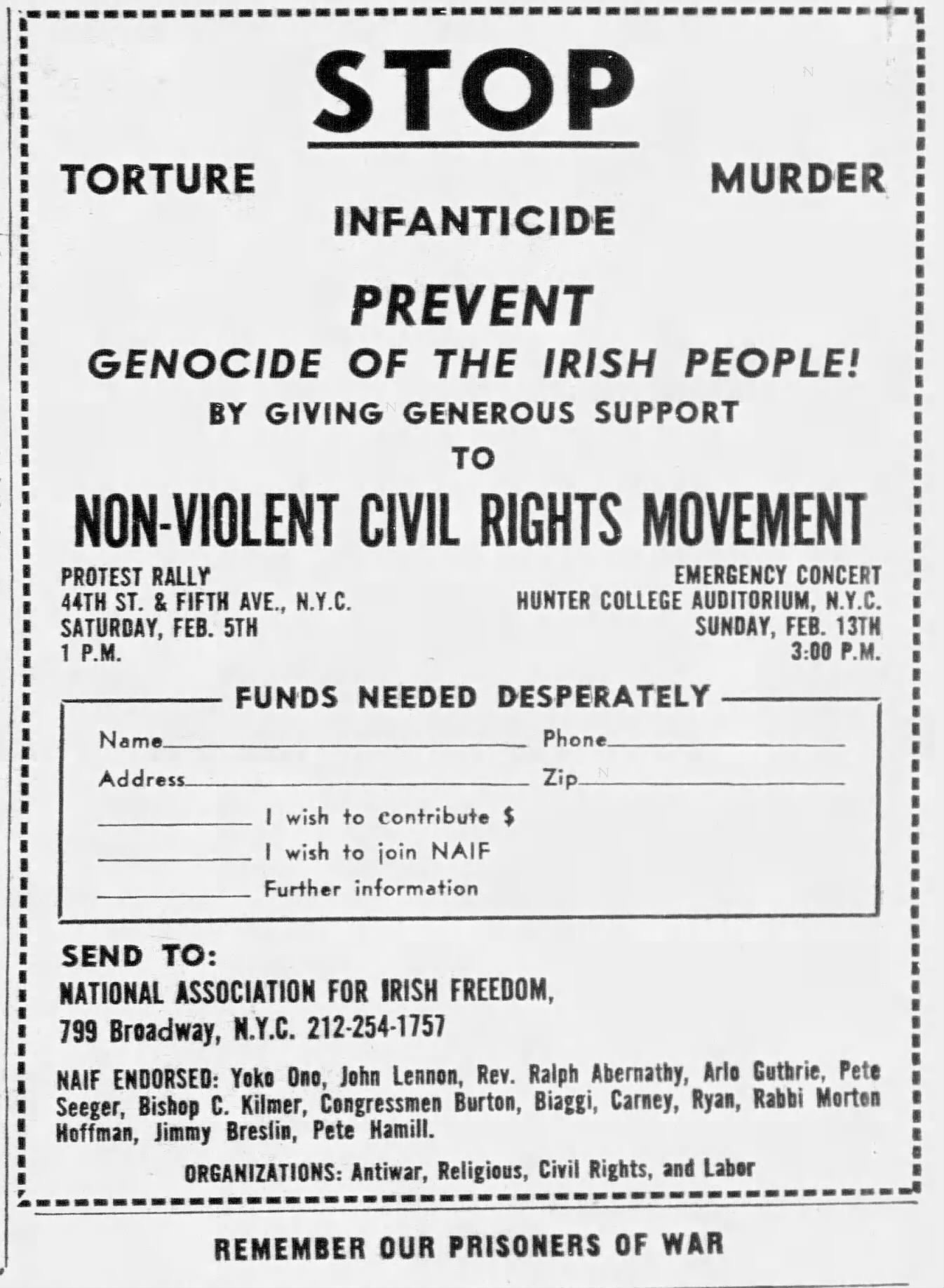

Since moving to New York with Yoko in '71, John had been hanging around with a rather colourful crowd that made the FBI's filing clerks work overtime. There was Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and the whole lot of them – the type who'd rather burn their draft cards than their incense. John had taken to showing up at anti-war rallies, using his celebrity status like a megaphone for peace. "All we are saying is give peace a chance," he'd sing, and thousands would join in, much to the discomfort of the Nixon administration.

The powers that be in Washington weren't exactly thrilled about having an ex-Beatle leading choruses of peace songs while they were trying to maintain support for their operations in Southeast Asia. It's worth noting that this was the same administration that had previously declared war on drugs, which seemed to conveniently target their political opponents more often than not. Now they appeared to be declaring war on a former moptop.

Here in Britain, the newspapers are having a field day with it all. The Daily Mirror's front page is splashed with some nonsense about the Common Market, but tucked away on page six is a small piece about John's troubles. It's fascinating how our prodigal son has become America's problem child.

Meanwhile, on this particular Friday, while bureaucrats are plotting his removal, John is probably waking up in his Bank Street apartment in Greenwich Village, blissfully unaware of the memo that would eventually become part of his FBI file. He's been working on some new material, trying to distance himself from the shadow of his former band while simultaneously fighting to stay in the country he's chosen as his new home.

The irony isn't lost on anyone that while John is being labeled dangerous in America, back home he's practically part of the establishment now. The same establishment that once feared his influence on youth culture is now more concerned with David Bowie's latest outrageous costume than anything John might be up to.

The cultural landscape has shifted dramatically since the heady days of Beatlemania. On this particular Friday, Radio 1 is playing T. Rex's latest, "Telegram Sam," while some new outfit called Slade is making noise on the charts. The kids queueing up at the local record shops aren't looking for "Please Please Me" anymore – they're after something called "glam rock," all platform boots and glitter.

But John's not interested in any of that. He's got bigger fish to fry, trying to make his voice heard above the din of Vietnam War protesters and FBI surveillance. The same voice that once sang "Help!" is now shouting "Power to the People," and it's making the men in Washington rather nervous.

What's particularly fascinating about this whole deportation business is how it exemplifies the paradox of John's relationship with America. Here's a man who fell in love with the country through its music – through Chuck Berry and Elvis and all those rock 'n' roll records that made their way across the Atlantic to a young lad in Liverpool. Now he's being told he's not welcome in the very place that helped shape his musical DNA.

The memo itself is a masterpiece of bureaucratic doublespeak. They can't very well say "we want him out because he's making us look bad," so instead, they dress it up in terms like "political views and activism." It's the kind of language that makes you wonder if they've got a special department for coming up with euphemisms

Up and down the country, in BBC studios and local radio stations, DJs are spinning the latest hits, completely oblivious to the political drama unfolding across the pond. Tony Blackburn's still chattering away about the latest Sweet single, while John Peel is probably at home planning which underground prog rock album he's going to inflict on his listeners tonight.

On the telly, viewers are settling in for another episode of "The Generation Game" with Bruce Forsyth, or perhaps catching up with whatever's happening in "Coronation Street." The juxtaposition between the cosy comfort of British entertainment and the political machinations targeting one of our own in America couldn't be more stark.

Let's be honest – John's always been a bit of a trouble magnet. This is the same bloke who caused an international incident by suggesting the Beatles were more popular than Jesus. The same one who sent back his MBE as a protest against Britain's involvement in Biafra and Vietnam. But there's something different about this latest controversy. It's not just about John being John anymore; it's about the fundamental right to dissent in a democratic society.

The truth is, John could have had an easier life. He could have stayed in England, knocked out a few more singles about peace and love, maybe done the occasional charity concert. Instead, he chose to plant his flag in New York City and fight for what he believed in, even if it meant taking on the most powerful government in the world.

As I sit here listening to the rain tap against my window, I can't help but think about the strange journey that led us here. From the Cavern Club to the Top of the Pops, from "Love Me Do" to "Give Peace a Chance," from Liverpool to New York City – it's been a long and winding road indeed. And now here we are, watching as the US government tries to silence a man whose greatest crime seems to be asking people to imagine a world without war.

The radio's playing "Imagine" now – speak of the devil – and there's something almost comical about hearing those lyrics about no countries while their author is being threatened with expulsion from one. But that's John for you – always living in the contradiction between what is and what could be.

In the coming days, this memo will set in motion a series of events that will dominate John's life for years to come. The battle to remain in America will become his new artistic expression, his new form of protest, his new revolution. And somehow, you get the feeling he wouldn't have it any other way.